27 & 29 High Street is the only known double-fronted building, built in 1866 by Edward Silcocks the Rode builder.

28 High Street (The Blake). Michael Sparey’s grandfather helped to convert many of the Fussell Brewery buildings, including the stables next door to the Blake. Michael Sparey lived in the Blake when he was growing up and he says there used to be a door from the side of the cottage that went into the stables (the ‘Hedgehog Factory’ in 2000 and now Choc on Choc). It makes sense to presume that at one time someone who worked in the stables also lived next door at the Blake.

Before Gwenda Finch restored her cottage in 1964, it was lived in by an elderly woman named Caroline Grant who had lots of cats. She was deaf and she couldn’t speak. Lois Hughes was her friend and she learned sign language so that she could ‘talk’ with her.

30 High Street (The Noffery). In 1964 The Noffery and the Blake were made from three separate cottages which were just about to be torn down. From architectural details, which still remain, it appears that the oldest part of the Noffery is that which is now to the right of the front door. When it was built in the early 1600s this cottage did not face on the High Street as it does now, but instead stood at a right angle to the street. The building was two storied, but there was also an attic room with at least one window.

At the rear in the single gable facing the garden is the last remnant of an old window head which dates from the early 1600s and perhaps even earlier. The old window originally had an ovolo moulded wooden surround, which was almost certainly in oak for it to have lasted so long, and two lights with a vertical iron bar in each light to hold diamond shaped leaded cames and glass. The old roof truss in this part of the house is probably the most helpful dateable feature. This truss has a tenoned apex joint, with a square ridge pole housed diagonally and suggests a date of about 1600. Also in the oldest part of the building is an inglenook fireplace that is probably from the same sort of date. It appears as if there originally would have been a set of stairs which wound around the back of the Inglenook.

You can see in the interior stone wall where the doorway has been filled in. (The outside of this circular stairway can still be seen in the cottage next door). The walls in this part of the house are all at least 24” thick. From deeds, it seems that James Moore, blacksmith and ironmonger, bought the old cottage from the Rose family in 1820. It was about this time that the building was radically altered, extended along the street frontage and refaced to give it today’s general appearance. The 1839 map shows that the coach house (today’s garage) did not yet exist and there was a passageway between 30 High Street and what is now 30A. This passage led to the rear of the properly where there were outbuildings described at various times as a blacksmith or ironmonger shop or stables. In 1861 the business was described as ironmonger & smith, draper & grocer. James Moore died in 1864 and his son Henry took over the business. (On 19 March 1863 at the Petty Sessions, Henry Moore, grocer of Rode was summoned for: “that on 27th February he had in his possession a 4 lb. iron weight 14 drams deficient and unstamped.” Moore was fined ten shillings).

In 1891, James Goulter bought the property. When he died in 1923, he left the property to his daughter, Caroline Louisa Goulter Noad. She was a teacher at the Wesleyan Day School. In 1951 Caroline was living as a tenant in one of the cottages, and Mrs. Price and Mr. Hill were in the other two. Mr. Paul Stacey remembered Caroline Noad living in the cottage next to the garage when she was quite elderly. In 1964, Alfred Dennis Carver rescued the three cottages, which were derelict by this time and he restored them. He combined two cottages to make the Noffery. The third cottage is now The Blake.

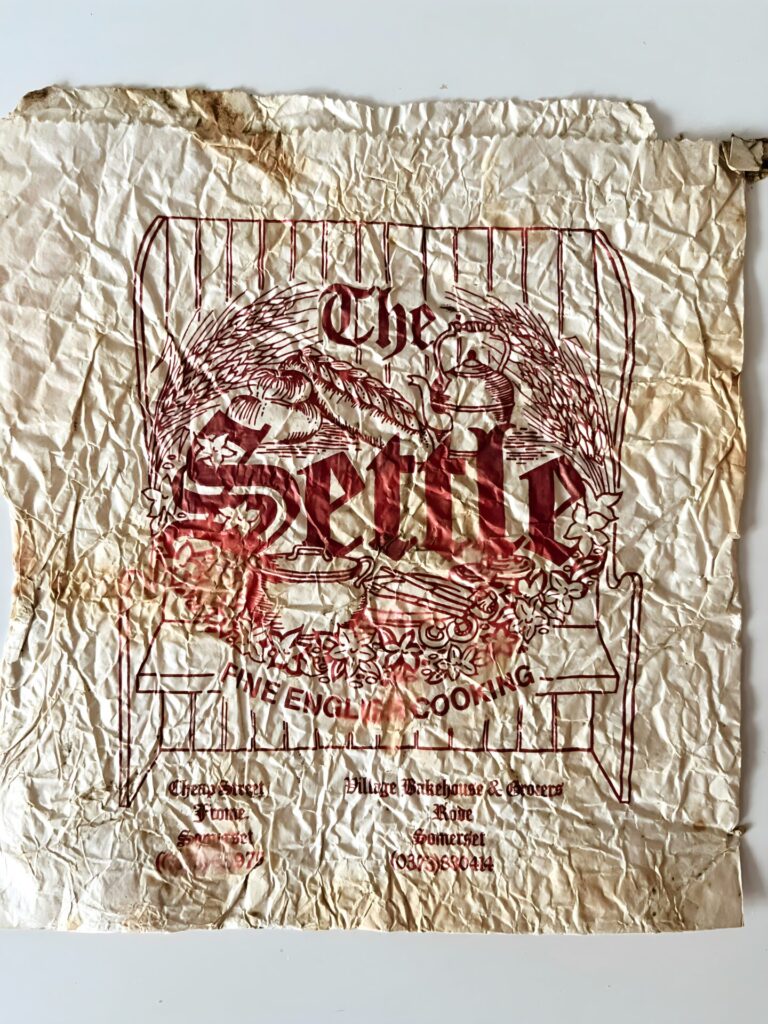

30A High Street and 32 High Street. The last owners said that when extensive repairs were made to the property early in the 1990s, medieval stonework was found as well as 17th century iron struts that were used to repair the ancient oak trusses in the roof. In the mid 1990s, the Andrews divided the property into two dwellings. There has been a bakery here since the last century at least. In 1861 James Henry Goulter, grocer/baker, lived here and had his shop; he was still here as late as 1919, but he died on March 24, 1923. By 1931, George Millard, baker, lived here. The Vaughan’s were the last bakers before the building was sold (Margaret Vaughan owned the bakery, and it was run by her daughter, Jude). After the sale, the Post Office was moved from opposite the Chocolate Factory to where it is today. The picture below shows an old paper bag (rather creased!) from the latter years of the building’s life as a bakery (you can just make out the text on the lower right: “Village Bakehouse & Grocers. Rode Somerset”.)

31 High Street This is a 17th century structure with early 19th century alterations. Features include the chamfered stone-mullioned windows and the plain stone door surround with moulded slab hood on cut stone brackets.

Old School Room was built as a Sunday school for the Baptist Chapel and the year 1839 is carved above the door. Samuel Norton was its first superintendent and is buried in the chapel graveyard next to the school. Edwina Davis says that during W.W.II, it was kept as a food store in case of air raids. In the 1950s, it was a British Legion waste paper store. The building was sold off in 1989 to raise money to repair and update the Chapel following a severe gale.

33 High Street is also a 17th century building with early 19th century alterations. From at least 1910 to 1926 it was known as Khartoum House and Arthur Cummins Wood lived here. In 1926 the owner was Gordon Henry George Cummings, who became village postmaster and converted the front room into the village post office. Note the old post box in the front wall. Later sub-postmasters in this post office were M. D. Franks 1929 to 1937, Julia Ashworth 1948 to 1949, C. J. Weedon 1949, and W. D. Bishop 1955 to 1958. Stories abound that it was at one time an inn or pub known as the Brassknocker Inn.

Extract from A History of Brewing in Rode by Sidney Fussell and Brian Foyston, 2006: “The Brass Knocker: Hearsay is that this was what is now 33, High Street. If so it must have been a long time ago, for it was the Post Office as far back as 1902, and as the local Methodist Minister lived there in the late l9th Century it certainly wasn’t selling liquor then!”

Hughes Court

3 Hughes Court (Japonica House). The front part of Japonica House was for many years a shop. As early as 1806 Samuel Fricker owned a bakehouse and house here. In 1843, the property was described as a house, shop and garden owned and occupied by Jacob Bourne. He also owned a shed and yard where Pound Cottage now stands. On March 24, 1874 there was a destructive fire at the shop which was then operated by Miss Hodges, draper and grocer. (While doing work in the cellar recently, builder Maurice Webb found evidence of the fire. He said that for sure the first floor had to be replaced as there is evidence of a Victorian replacement). However, the fire was more extensive than that. The fire was discovered about 9.00 in the evening. Within minutes of raising the alarm, the whole premises were on fire. Flames shot from upper windows and through the roof and they illuminated the streets. A large crowd quickly gathered and they did all they could to bring the fire under control; but within two hours, the place was in ruins. However, the fire did not spread to the adjacent thatched cottages but was contained to the shop and house of Miss Hodges. So apparently the building as it is seen today is Victorian.

By 1883, the business was owned by George William Stokes. Some time between 1883 and 1889, the post office moved from the shop at Townsend to this shop. The Kelly’s Directory for 1898 described the business in this way: ”draper, furniture dealer, grocer, provision merchant, outfitter, complete house furnisher and general factor, dressmaking, millinery and tailoring, post office.”

In the cellar, they used to make candles. Mr. Stokes was here at least until 1924. He had also been chairman of the Parish Council from soon after its conception in 1895 until he retired. By 1926, Mrs. Ethelyne Eva Small ran the shop and from 1939 to 1945 a Mr. Watt rented the business from her. After that the shop was run by George Henry Day, who became owner in 1952. Then his daughter, Lois, and Edward Hughes took over when they were married in 1955. An article written for “The Lady” magazine by Stephanie Johns of Frome, described the shop as follows:

“Almost any item that a household needed could be bought over the heavy mahogany counter, from a pennyworth of pear drops to a bath cap! Duplicate books allowed purchases to be listed and paid for at the end of the week. The long columns of figures would be swiftly added up entirely without the use of computers or electronic tills. The whole of the village shopped here, some every day and most several times a week. Unexpected absences were soon investigated through a mixture of concern and curiosity.”

In 1986 the stores were finally closed and the property was made into dwellings.

4 Hughes Court (Laburnum Cottage). There used to be a continuous row of cottages making up what is now known as Hughes Court. The 1806 survey records two cottages here, with one void and the other owned by William Hossier. In 1843 one cottage again was shown as void with the other owned by Ann Wheeler and occupied by George Caleb. On the ground floor of what is now Laburnum Cottage Lois Hughes told me (DP) there was a warehouse for the shop next door and upstairs was a large hall where they used to hold dances. Then in 1986, the property again became a cottage when Hughes Court was constructed.

5 Hughes Court (Magnolia Cottage).This building is shown as one cottage owned by William Hossier in 1806 and in 1843 by Ann Wheeler and occupied by Jeremiah Phillips. Some time before 1904 it was extended towards the road. Then it was used as a garage or coach house for the shop. The upper storey was part of the dance hall (at no. 4) and contained a full width stage for the band.

6 Hughes Court is listed as 17th century. The 1806 survey records it as two cottages, one behind the other, owned by Jane Quance, who also owned the land down to Lower Street. In 1843 they were still owned by Jane Quance and occupied by James Holcomb and Sarah Wasfield. Before the redevelopment of the area in 1986 it was a single dwelling numbered 39 High St.

8 Hughes Court, according to Michael Sparey, was rebuilt in 1908 after the original cottage was destroyed in a fire where an old woman lost her life. He said that previously there had been seven cottages of reed thatch built around a horseshoe shape, with 8 Hughes Court at one end. Indeed, if you look at the North Bradley Map for 1807 there is a complete row of cottages from what is now Japonica House to 8 Hughes Court. By the 1899 map, there was a gap between 8 Hughes Court and the other cottages which used to make up the same row. 8 Hughes Court used to be called St. Helen’s.

According to Mr. Sidney W. Fussell of Bratton, Mrs. Spittal moved in before 1920; in 1920-1923 Arnold Noad lived here and by 1935, Reginald G. Fussell was living here. He lived at St Helen’s until he had Ten Acres built on Crooked Lane in 1939. This was 41 High Street before the development of Hughes Court in 1986.

34 High Street was standing at the time that Spring Cottage (see 36 High Street, below) was built between it and The White Hart. It was probably one of the properties bought by John Wheeler in the early 1800s and passed down to Arnold J. Noad in 1930.

35 High Street is included in the listed buildings register for group value with other buildings on the High Street. It is thought to be early-19th century.

36 High Street (Spring Cottage). According to the Vernacular Architecture study done by Mr. Williams in 1985, this too was a hall house of at least early 15th century origin and, with no. 38, a rare example of adjoined medieval houses. The hall was re-roofed in the 15th century, and ceiled with an inserted fireplace in 17th century, when the west end was reroofed. The roof has reused timbers in places and most are soot-blackened. A couple of the trusses are of 7” square section and another 12”x7”—each a dressed tree trunk. The rubble walls are about 27-28” thick. At the east end is a (19th century?) bay window and an inserted cottage door (perhaps to make that end of the cottage into a shop). It is now the kitchen for no. 36. The porch used to be a two-storied one, as can be seen in the photo on the previous page.

In the attic floor over the hall are square wooden vent tubes which Mr. Williams said could be a possible indication of cheese storage. It is thought that Spring Cottage was built after the White Hart and no. 34. Ownership of this property has been traced back to 1672 when William Harris was granted a lifetime tenancy by the then Lord of the Manor. On his death in 1699 it passed to his son, Thomas, who sold it to William Stevens a yeoman of Wingfield. A deed of 1719 records that Stevens gifted it to his “sister-in-law”, Ann Frycker alias Stevens, and her children on his death, who sold it within a few months to John Pockeridge, a druggett maker in Rode. His daughter, Ann, married Samuel Miller and the property passed down through her descendants until it was purchased by John Wheeler in 1824. It was then handed down through the Wheeler family, like 4 Marsh Road and 38 High Street, until it was bequeathed to Arnold J. Noad in 1930.

38 High Street (White Hart Cottage). Mr. William Gosling provided the following information. A drawing of 1815 refers to it as ‘formerly’ the inn. This house is one of the oldest in Rode Village. Dated by roof wood-joints (by the late Cdr. Williams), the earliest part is late 14th or early 15th century. At first a single storey hall, with a central hearth and a gallery at the east end (probably reached by a ladder), its entrance door may have been beneath the gallery – now an alcove containing bookshelves. The original gallery forms the floor of the present solar, its level lower than others upstairs. In the 16th century the principal fireplace and chimney were built, breaking the hall in two, but making it practicable to have an upper floor. The fireplace has a bread oven, but the mantel-beam, originally carved, has been crudely defaced, probably during the Puritan period.

The present outer hall has the old gallery for its ceiling, although timbers have been much replaced. The coffered ceiling in the inner hall is thought older than 16th century, perhaps taken from another building. In the stone windows, sockets will be found for the vertical wooden bars, common before glazing. The inner part of this room (plain ceiling) was probably a parlour. The kitchen replaces a smaller early buttery, the roof line of which can be seen from outside in the stones of the back wall. It was enlarged when the back wing of the house was built, in the late 17th or early 18th century (dated from construction techniques). The small circular window at the rear of the Aga stove perhaps corresponds to the original buttery door.

The spiral stairs are oak, 16th century, and unusual for the date in their sense of rotation. The turned banisters at the upper floor are of a typical 17th century pattern. At the head of the stairs is a gallery, now used as a study, with a revealed original true cruck. Notable here is the wide boarded floor – the boards mostly split, not sawn. Similar floors (now carpeted) are found through the front (old) part of the house. Opening from the gallery is the solar (step down) with an interesting small fire-place of uncertain date. This room has a partly revealed cruck, also the unusual ‘Trinity’ door, originally of religious significance, made of three different woods. The back extension is 17-18th century, re-partitioned in recent times in deference to the contemporary dislike of communal sleeping.

The west wall of the main bedroom and bathroom is a modern partition, hiding another true cruck. Outside, the house retains its original character, although the split stone roof was replaced by tile about a hundred years ago. Across the back yard is the much re-constructed brew-house, typically built on two levels with ‘L’ plan (now used for storage, garage and laundry). Two tiny cottages at the back of the house were demolished some years ago to create a small walled garden. Also in the back, is a medieval well. Village tradition says that Oliver Cromwell slept here. If so it would have been in the present solar, and probably in the first week of September 1645, when, having just reduced Bristol, he was moving slowly across country, resting himself and his men, before the conquest of Devizes. A recently discovered deed dated 4th April 1737 describes the property as:

“All that Dwelling house in Road aforesaid wherein the William Stevens the elder now lives being a Public Inn and called or known by the name or sign of the New Inn and also all that malthouse newly erected and built in the backside of the said New Inn”

By 1777 it was called the White Hart Inn and in 1802 was sold to John Wheeler as a private house. It was then handed down through the Wheeler family, like 4 Marsh Road, until it was bequeathed to Arnold J. Noad in 1930.

Extract from “A History of Brewing in Rode” by Sidney Fussell and Brian Foyston, 2006:

“The White Hart:

The very name of this delightful cottage at 38, High Street (formerly No. l, The Green) evokes the image of a Pub and the present owners can point to a well-preserved plan of the ground floor which supports this. to which can be added, across the back yard, the much reconstructed brew house, built on two levels as was typical of buildings of the type in those days. Lore has it that both the Duke of Monmouth and Oliver Cromwell made brief sojourns at the cottage. However it is not mentioned in any of the 19th century Directories, nor is there any mention of brewing in the Will of John Wheeler the Elder, dated 14th January 1815, who, dying in 1818, left the property and its adjoining cottages to his married daughter Elizabeth Dawson. We can thus deduce that brewing at the White Hart ceased in the late 18th or early 19th centuries (see notes below) (perhaps another indication of current ‘hard times’). Ref.2 has much more about this fascinating house.

The sign of the White Hart, so myth has it, dates back to the time of Alexander the Great (356-323 BC), when he met with such an animal while walking in the forest. He put his gold chain around her neck and led her back to his camp. As with so many tales the central figure has changed over time, from Alexander to Diomede, to Julius Caesar and to Charlemagne and others. The White Hart was also the badge of King Richard II (1361 to 1400AD).”

43 High Street (Prospect Villa). Reginald G. Fussell was living here in 1924 until 1933.

47 High Street

49-to 55 High Street. These cottages have a very different appearance than any of the rest in the village. Past residents were told that originally the building was a factory or workrooms. Indeed, the stairs go all the way up to the attic, spiralling around the back of the fireplace in no. 55. In the attic itself, there are wide wooden floorboards and old panelled partitions breaking up the space into two rooms. Only no. 55 appears on the 1806 map (See yellow cottage in figure 20), owned by John Wilson and occupied by Jeremiah Bailey.

Presumably nos. 49 through 53 were still under construction. Apparently some of the windows along the High Street were blocked up to save paying the tax on windows that was introduced at the end of the 17th century and not repealed until 1851. While it is true that some owners did brick up their windows to avoid paying tax, not all the blocked windows we see today in old houses are the result of this. Sometimes when a house’s internal features have been changed, windows have been blocked in where they weren’t needed. If the old structure had been a factory or workshop and was later made into dwellings, the windows could have been in the wrong place and so were then bricked in.

In 1843, the whole property was owned by Edward Craddock but the cottage now known as no. 49 was occupied by Joseph Wilson, no. 51 by Mr. Frees, no. 53 was unoccupied and no. 55 was occupied by James Goulter. In 1919 William James Morris, builder, carpenter and assistant overseer, lived at what is now 55 High Street. According to Edwina Davis, when he purchased the property, nos. 53 and 55 were one house. Eventually he made them into two separate dwellings, renting out no. 53. In the front room of no. 55 there is a window recess which the family refers to as the ‘glass case’ and it is used to hold china.

It looks like it could have been a window at one time. A recent owner of no. 55 found pieces of leather under the floorboards of one of the back bedrooms. Perhaps they had once belonged to John Goulter who had been a cordwainer here at one time. There is a well under the kitchens in nos. 51 and 53 and there used to be a pump in the back which supplied all the houses with water. One of the back bedrooms in no. 55 is over the kitchen in no. 53. Many years ago, Edwina Davis said there was a painting found rolled up and put between the wall boards in the attic. It had Barrow House written on it. As the house was torn down sometime in the late 1880s, that picture must have been painted sometime before. Edwina Davis also said she remembers her father telling her that when he was small he saw Constance Kent, who confessed to the Rode Murder, being led into the Sheriffs house at no. 57 in handcuffs. In the early 1930s the village postman, Mr. Lambourne, lived at no. 53 and he later moved to no. 49.

57 to 65 High Street. Although some of these houses have been listed as 19th century, they appear on the 1792 map as a single long terrace of dwellings. In 1806 the terrace appears as nine cottages, the northern most owned and occupied by William Wheeler and the others owned by Jonathan Noad. There were also nine cottages in 1843.

57 High Street is a 17th century house. In his will dated 1809 Jonathan Noad left this property, then occupied by Benjamin Craddock, to his daughter Ann Rose. By 1843 it was two cottages owned by Ann’s widower, Joseph Rose, and were occupied by Ann Millett and Thomas Holton. In 1857 it was owned by Thomas and Ann Rose, children of Joseph and Ann, and occupied by Sidney Norton and William Chivers. Later that year William Wheatley, policeman and son of the well-known local painter, had replaced Sidney Norton.

59 and 61 High Street are listed as a pair of early 19th century attached cottages but appear on the 1792 map. In 1806 they were occupied by Steven Yerbury and Mr. Randall. By 1843 they were owned by Eleanor Noad, a daughter-in-law of Jonathan Noad, and occupied by James Jones and William Randall.

63 High Street was two cottages in 1806, owned by Eleanor Noad and occupied by James Jones and George Parker. By 1843 John Hillman and Thomas Rose were living here. It is listed as an early 19th century house and shop. By 1881 the shop was occupied by Virtue Noad, nee Fussell. Her husband had died in 1880, aged 32, and Virtue continued running the shop until 1889

65 High Street and Forge Cottage. These are listed as 18th century with Forge Cottage having been the village forge. They were occupied in 1806 by John Say and John Tanner. By 1843 they were three cottages owned by Eleanor Noad with James Hosier and James Smart living in two and the other unoccupied. Forge Cottage used to be the carriage house for Irondale, which is next door.

Dower Cottage was the workshop where Henry Prosser built organs for St. Lawrence and Christchurch. Paul Stacey remembered playing in the vacant building when he was a small boy. Percy Fussell bought it in 1941 and restored the building.

71 High Street (Fairview). There was a house here in 1806 owned by Joseph Cabell, who also owned most of the land between High street and Lower Street. By 1843 it was owned by Ann Wilson and occupied by John Stevens. It was then called Fairview Villa. From at least 1895 to 1903 it was lived in by Mrs. Stokes, senior. Sometime before 1915, it belonged to Mr. Prosser the organ builder. From 1926 to 41, the house belonged to the Methodists and then the Fussells until 1961. However, Paul Stacey’s family lived in it from 1926-1984.