The Road Hill Murder 1860

Summarised by Terry Silcock and edited by Peter Harris

Based on information published in various sources:

Cruelly Murdered – Constance Kent and the Killing at Road Hill House by Bernard Taylor, pub by: Souvenir Press 1979 ISBN 0-255-62387-7 (this has a list of the main characters at page 13/14 and map on the end covers).

There have been other books on the subject:

The Great Crime of 1860 by Joseph Stapleton pub1861 @ East Marlborough

The Case of Constance Kent by John Rhode pub by Geoffrey Bles in 1928

Saint with Red Hands by Yseult Bridges pub by Jarrolds 1954; ( pub in USA as The Tragedy of Road Hill House by Reinehart in 1955)

Note: In 1860 the village of Road was split between two counties. Most of the village was in Somerset but part, including the area called Road Hill, was in Wiltshire.

Background

Samuel Savill KENT born 1801, son of a prosperous carpet manufacturer, Samuel Luck KENT, who was in business at London Hill. His mother was ? SAVILL, daughter of property owners in Colchester, Essex.

In about 1826 he met Mary Ann WINDUS daughter of Thomas WINDUS, a wealthy coach builder, of Bishopsgate St., London. They married at St. Johns Church, Hackney on 8 Jun. 1829. They lived in Artillery Place, Finsbury Park.

Their children were; Thomas Savill KENT (1), born December 1830, died of convulsions January 1832 ; Mary Ann Alice KENT (2), born October 1831; Elizabeth KENT (3), born December 1832; both were strong and thrived.

Samuel S. KENT’s health declined and the family moved to Cliff Cottage, Sidmouth, where he became a sub-inspector of factories, implementing the 1833 factory acts. His wife, Mary Ann, was seriously ill before the birth of their fourth child, Edward Windus KENT (4), born April 1835; followed by Henry Savill KENT (5), born February 1837, died May 1838.

In 1839 a governess had been hired for Mary Ann & Elizabeth; Mary Drew PRATT born 1820 the third of four children to Francis PRATT, a grocer, and Mary, of Tiverton, Devon. Further children were born; Ellen KENT (6), born September 1839, died December 1839; John Savill KENT (7) born March 1841, died July 1841; Julia KENT (8) born April 1842, died September 1842; Constance Emily KENT (9) born 6th February 1844; and William Savill KENT (10) born July 1845. At this time Mr KENT suggested that his wife was insane, but in 1850 their parlour maid, Harriet GOLLOP, thought that Mrs KENT was unhappy, but not insane. Mary PRATT soon became Mr KENT’s mistress. This scandal caused the family to move in 1848 to Walton Manor, a spacious secluded mansion in the village of Walton-in-Gordano, near Clevedon, Somerset. But by March 1852, gossip had forced them to move on again to Baynton House (20 rooms) at East Coulston, near Westbury, Wilts. On 1st May 1852 Mary PRATT left to visit her father who was ill in Tiverton, Devon. The next day Mrs KENT became desperately ill with excruciating stomach pains, and died in agony at Baynton House days later. Mary PRATT’s father died on 15th May 1852. After a while Mary PRATT’s mother also died. A stone was placed in the East Coulston churchyard in memory of Mary KENT.

On 11 Aug. 1853, Mr KENT married his “governess” at St Mary’s church, Lewisham; from her uncle’s house, which was nearby. She claimed to be of Lewisham. Constance KENT and her 2 sisters (Mary Ann and Elizabeth) were bridesmaids.

Mary KENT’s first child (11) was still-born in June 1854.

Edward KENT (4) had entered the service of the West India Royal Mail Steam Packet Co. in about 1850. In Nov. 1854 he was reported as having drowned off the coast of Balaclava, when his ship, Kenilworth, sank with all hands, but he later returned having been one of the few to escape to the shore.

Mary Amelia KENT (12) was born in 1855.

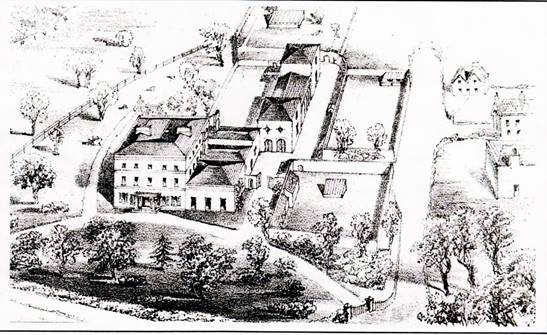

In the autumn of 1855 the family moved to Road Hill House, (built in 1790) at Road Hill, Wiltshire. Just before they moved in Mr KENT found a local lad, Abraham NUTT, scrumping apples and he started a prosecution against him.

In 1856 Constance KENT (12.5y), disguised in boy’s clothes, and William (11y) tried to run away to sea, but they were caught at the Greyhound Hotel in Bath.

Francis Savill KENT (13) was born in August 1856, he was normally known as Savill K. Edward KENT (4) died of yellow fever on board his ship, CLYDE, on 11th July 1858. He had written a will leaving his money (£300) to his siblings.

Eveline KENT (13) was born in October 1858.

In 1859 Constance KENT was removed to a school at Beckington, run by Miss SCOTT, with an assistant Miss WILLIAMSON.

On the 29th June 1859 the three main servants at Rode Hill house were; Sarah KERSLAND, cook – general; Sarah COX, young house maid; Elizabeth GOUGH, children’s nurse. EG born c1836 was the daughter of William GOUGH, a respected Isleworth baker.

Additionally; Emily DOEL (14y) a local girl came in daily assisted Elizabeth GOUGH; and Mrs. Mary HOLCOMBE came in on Saturdays & Mondays to do scrubbing in the kitchen area.

There were also three outdoor male servants; James HOLCOMBE (son of Mary) who worked when required as a groom/gardener; and Daniel OLIVER of Beckington, an elderly casual helper.

John ALLOWAY had handed in his notice, because his request for a raise had been refused. Henry TOLER a sweep from Trowbridge had swept three flues (paid 4/6d)

and Tom FRICKER an elderly general labourer and jack of all trades had been repairing Mr KENT’s “Dark Lantern”.

In the 1860s, William GEE of Freshford wrote that Mr KENT was living beyond his means and could not pay the school bills. There was a very high turnover of servants in the Kent household. Over 200 different female servants in four years at Road Hill House.

In the period 1840-1860, there had been 5 cut-throat murders in the area of Road.

The Crime (night of Friday 29th June 1860)

During the night P.C. URCH of Somerset Constabulary based at Road, was on duty until 12.50.

A nearby resident, Joe MOON, and his companion heard barking dogs. They worked at the local lime-kilns, but were out poaching trout from the river.

At 7am on the Saturday morning Saville KENT could not be found. The drawing room windows and shutter were open, and the cot had been slept in.

Mr Kent got up and got HOLCOMBE to fetch Constable URCH. Mr KENT then decided to go into Trowbridge, Wiltshire to get Superintendent FOLEY (It must be remembered that Road Hill House was in Wiltshire). He also sent his son William for a constable. William met Thomas BENGER, a smallholder, and James MORGAN, a baker and also a parish constable at his shop. URCH was a Somerset constable although his house was in Wiltshire.

The news spread quickly through the village. A passing neighbour, Mr GREENHILL, told William NUTT, a shoemaker and the district clerk. Abraham NUTT, brother of William, had earlier been prosecuted for trespassing on Mr KENT’s land. NUTT & BENGER searched the garden and then the outside privy. They lifted the seat and eventually found Savill KENT at about 8 a.m. with a blanket wedged between the splash board and the back wall. His throat had been cut from ear to ear. Just before Rev. Edward PEACOCK, arrived from the nearby Vicarage.

Meanwhile at Southwick Mr KENT paid the toll to Mrs Ann HALL, the turnpike gate keeper. She told him the nearest policeman was P.C. HERITAGE, Mrs HERITAGE saw Mr KENT passing by.

When Savill KENT’s body was brought into the house William was sent to Beckington to summon Dr. PARSONS, the surgeon. The county coroner, George SYLVESTER, was contacted to authorise a post-mortem. Some time after 9am, Supt. John FOLEY arrived with P.C.s HERITAGE & DALLIMORE. Thomas FRICKER was called to empty the garden privy’s vault. Stephen MILLETT a local butcher and parish constable assisted with the search. At about 11 am, Roland RODWAY, Mr KENT’s legal adviser, arrived with Dr. Joseph W. STAPLETON, a surgeon to the local factories under Mr KENT’s jurisdiction. At about 2 p.m., Sergeant James WATTS of Frome police force arrived. P.C. DALLIMORE’s wife, Eliza, arrived from Trowbridge to search the females present. Later that afternoon Mrs SILCOX (?Anna tmbs), the undertaker’s mother, began her task of laying out the dead child. The next Monday, everyone went to Road Hill House, including Captain MEREDITH, Wiltshire’s Chief Constable.

The inquest

It was held on the next Monday at the nearby Temperance Hall, but this room was too small so the inquest was transferred to the Red Lion Inn.(No, transfer was from Red Lion to Temperance Hall – Peter Harris) The coroner was George SYLVESTER, foreman of the Jury, Revd. PEACOCK, PC DALLIMORE of Trowbridge and his wife attended. Also attending were Rowland RODWAY (Mr K’s solicitor). Some of the jurymen, including WEST & MARKTS, were reluctant to sign the verdict, “Murder by persons unknown”.

Later Events

Mrs Esther HOLLY and her daughter Martha went to collect laundry from Rode Hill House, they found that Constance’s night dress was missing from the laundry.

Savill KENT’s body was buried on Friday 6th July in the family grave at East Coulston.

Samuel GOUGH, Elizabeth’s father, came from Isleworth for the examination of his daughter, Elizabeth had been staying at the saddler’s house in Road, with the saddler’s sister, Ann STOKES. Constance KENT reported that on the Friday she had walked over to Beckington to pay a bill, and had visited Miss BIGGS and Miss WILLIAMS, but she had not visited any shops.

Inspector WHICHER of Scotland Yard was called in and eventually arrested Constance KENT. Constance was “tried”, with WHICHER prosecuting. One of Constance’s school friends, Emma MOODY, gave testimony. After the examination Constance was released, with her father entering into a bond of £200, for her to appear if called again.

In August, a further enquiry was set up by a Mr SLACK, he examined many people including Emma SPARKES, a former servant of the KENTs. Elizabeth GOUGH had returned to South Street, Isleworth with her father. But on 28th September, Supt. WOLFE travelled there with a warrant for her arrest. This inquiry began on 1st October and lasted four days. Additional witnesses were; John ALLOWAY (Mr KENT’s odd job man), Daniel OLIVER (a jobbing gardener). Elizabeth GOUGH was discharged, but her uncle Arthur SPACKMAN of Blackheath put up bail for the whole sum of £100. It was reported that an Elizabeth GOUGH of similar description had worked in1858-9 for a Mr HAWTREY of Eton, but she had been an “artful” girl and had been discharged owing to her misconduct. Soon afterwards Constance Emily KENT departed for France where, at Dinan, she was registered as Emily KENT at a fashionable finishing school.

In July 1863, Constance Kent was accepted as a guest at 2 Queens Square, Brighton (St. Mary’s Home), which was a convent and hospital affiliated to St. Paul’s Church, Brighton. It was organised by Rev. Arthur WAGNER, the perpetual curate of the church. He was a “Puseyite” (very high church). The Superior of the convent was Katherine Anne GREAM. Constance took confirmation, probably in 1864.

On 6th February 1865, Constance confessed to the murder in her confessional and authorised Arthur WAGNER to inform the Home Secretary. She requested to be taken to Bow Street (24th April) when her confession was accepted and she was then transferred to Trowbridge and appeared before the magistrates at the Police Gaol on 26th April. She was taken to Trowbridge Police Court on 5th May. Many of the witnesses and others involved had changed in the previous five years. Sarah COX (housemaid) had married George ROGERS, a farmer of Steeple Ashton in the early summer of 1863. Jonathan WHICHER the Scotland Yard Detective had retired and now lived quietly at Salisbury. Sup John FOLEY of Wiltshire police force had died in June 1864, of dropsy in the chest.

The Trial

Constance KENT was brought into court by Inspector GIBSON of Melksham Police and Mrs ALEXANDER the wife of the gaoler. Mr RODWAY was representing Constance KENT. The court committed her for trial at the next Wiltshire Sessions, to be held at Salisbury on 19th July 1865.

At the trial Constance pleaded guilty, admitting that she killed Savill to get her revenge on the person who had usurped her mother in her father’s affections. Considering that this was a greater revenge than killing her step-mother. But in the five years since the event she had repented and so had confessed as an atonement. Despite pressure from the judge, Mr Justice WILLES, she refused to change her plea and emphasised that she alone had been party to the crime. So the judge had no option but to pass the death sentence. The trial had only lasted a few minutes. The judge submitted a recommendation for mercy to the Home Secretary.

On 25th July, the Home Secretary: Sir John GREY, after consulting with the Cabinet, announced that the death sentence was commuted to penal servitude for life, because if she had been tried at the time of the crime she would have been only 16 years old and she was only convicted by her confession.

A Dr BUCKNILL wrote a letter to the press in which Constance KENT confessed how the crime was committed and her motive – the possession of a devil. However, later he disclosed the true motive, she was taking revenge on her step-mother for disparaging remarks about her mother.

The book critically analyses her confession as to how the murder was committed and concludes while certain parts of it bear signs of truthfulness, it must be acknowledged that other parts were the result of deliberate lying or hasty innovation. The author then expands his theories. He concludes that Constance KENT made a fuller confession to Rev WAGNER, but only authorised him to pass on her confession of guilt which specifically emphasised only her involvement. The author provides a dramatic reconstruction of his hypotheses of the murder and those who were involved.

Subsequent Events

Madame Tussaud’s waxworks put an effigy of Constance KENT on display.

Constance was initially detained at Salisbury Gaol, until there was sufficient space to move her to Millbank Prison in London. At the time of her crime a life sentence was for at least 12 years, 15 years without remission. After an initial period at the prison she was employed in the laundry and later in the infirmary tending the sick.

Meanwhile, Elizabeth GOUGH married a Kensington wine merchant, John COCKBURN, at St Mary Newington, Surrey on 24 April 1866.

The Kent’s moved away to Llangollen. Mrs Mary Drew KENT fell ill and died on 17th August 1865, of congestion of the lungs aged 46 years.

Samuel KENT and the younger children moved further north in Wales to Llanynys, Denbigh. Samuel died on 5th February 1872, from disease of the liver aged 72 years. He was buried beside his wife in Llangollen churchyard. The older children had already left home, Mary Ann and Elizabeth living together.

William KENT was working in London as a naturalist. In 1872 he was working at the British Museum. Later that year he married Elizabeth BENNETT, daughter of Thomas Randle BENNETT. The latter appealed to the Home Secretary for Constance’s release from prison, which was denied.

By this time Constance had been transferred to Parkhurst Prison. She was working on mosaics for churches; Bishops Chapel, Chichester, St Pauls Cathedral, East Grinstead Parish Ch and St Peters Church, Portland, Dorset. She was later moved to Woking prison and then back to Millbank. It was then realised that at the time of her sentencing, life was at least 20 years. In 1877, 12 years after her trial, the family pleaded her case and submitted a petition for release. This was followed by further unsuccessful petitions in 1878, 1880, 1881, 1882, 1883 and 1884.

Meanwhile William KENT’s wife Elizabeth had died in 1875 at 25 years old. In 1876 he remarried, Mary Ann LIVESEY. In 1884 they emigrated to Tasmania as the “SAVILL-KENT” family with his half-sister Mary Amelia (29y).

On the 16th April 1885 Constance submitted her seventh petition, as a result of which a release on licence from Fulham prison was granted on 18th July 1885, 20 years from the start of her trial. On her release she was met by Rev. WAGNER, who escorted her by train to his home “Belvedere” at Buxted, Sussex, where he had established a religious community, affiliated to his St Mary’s Church.

In 1886 her brother William left Tasmania for England and returned there with Ruth Emilie KAYE, who the author claims was Constance KENT. She stayed with her brother when his family moved to Melbourne in 1887 and again in 1888 when they moved on to Darling Downs in Queensland. But she later returned to Melbourne. In 1890, during a typhoid crisis, the Alfred Hospital appealed for help. Constance began a nurse’s training course at 46 years old, which she completed in March 1892.

Her subsequent career may be summarised:

August 1892 matron at a private hospital, Perth WA.

November 1893 sister at Coast Hospital (Now Prince Henry Hospital) Sydney, NSW.

Later promoted to matron and transferred to Lazaret, an annexe for Lepers.

In 1898 (aged 54 y, but recorded as 49y) went to Mittagong – a TB sanatorium.

In 1910 , went to Maitland taking a lease on a property in Elgin St.

She reopened it as Maitland Nurses Home (previously and later known as: Pierce Memorial Nurses Home)

In 1929 a letter was received frother media. It was reported she was born at Waddon Manor, South Devon in 1844 one of 14 children. She died two months later on 10th April, of old age and was cremated. Sadly nobody claimed her ashes.

Meanwhile in 1896 William and his wife returned to England. He died at Milford-on-Sea in 1908.

The sisters Mary Ann & Elizabeth KENT were by 1896 living at Wandsworth. In February 1913 Mary Ann KENT died at East Hill Wandwsorth of bronchitis aged 81 years and Elizabeth KENT died in 1922, just before her 90th birthday. Both are buried at Putney Vale cemetery.

At Road, the privy and subsequent memorial arbor at Road Hill House have gone, although the house still stands, but now named Langham House and the village is now Rode.

The Red Lion Inn still stands but is now a private house and the Temperance Hall was demolished many years ago.

The headstones marking the graves of Savill KENT and the first Mrs KENT can still be found in Coulston churchyard, but are almost indecipherable.

TMBS 17 Nov. 97

Report from the New York Times on May 13th 1878, which includes the revelations of the doctor who examined Constance Kent to determine her sanity.

THE CASE OF CONSTANCE KENT

THE MYSTERIOUS MURDER NEAR FROME ENGLAND, 13 YEARS AGO—HOW AN EFFICIENT DETECTIVE WAS UNJUSTLY REWARDED—REVELATIONS BY A LONDON PHYSICIAN.

On the night of June 29, 1860, at Road, a little village near Frome, in Wiltshire, England, was perpetrated a most cruel and mysterious murder. There lived at Road a certain Mr. Kent, a sub-inspector of factories. His household consisted of himself, his wife, three daughters – Mary, aged 29; Elizabeth, 27; Constance, 16 – and a son William Saville, aged 15, all children by a former marriage. Besides these were also a daughter, Mary, aged 5; a son, Francis Saville, about 4, and an infant daughter, the offspring of the second marriage. One morning the family were startled by the nurse, who cried out that Francis was missing, and when search was made immediately the body of the little boy was found in an outhouse with the throat cut in the most shocking manner. The wildest and most improbable rumors were soon in circulation, and suspicion was fixed upon Elizabeth Gough, the nurse, and upon Mr. Kent. Miss Gough was arrested, but there being absolutely no proof against her the magistrate dismissed the charge. Of Mr. Kent it was said that he had killed the child to prevent its disclosing his own misconduct, and circumstances were ingeniously tortured to justify the conclusion. Then Whicher, a detective, was put upon the scent, and before he had had the case 24 hours in his hands the terrible secret was discovered. He obtained a warrant for the arrest of the young girl Constance, and had her brought before a magistrate on a charge of murder. The detective founded his case chiefly on the fact that one of Constance Kent’s night-gowns was missing; that there were circumstances leading to the conclusion that she herself had destroyed it, and that she had done so because it was stained with blood. The magistrate dismissed the case, and Constance was made a heroine. Every one was talking about her youth, beauty, innocence, and intelligence; every one was denouncing Whicher as a meddlesome incompetent, malicious mouchard, who had tried to put a handsome, accomplished, and innocent young lady on the gallows. More than this, he had been bribed by Mr. Kent to fix the crime on Constance, and so it happened that he had to leave the Police force, while the father was for some time in positive danger.

After her acquittal of the murder, Constance left home and went to live as a visitor or novice in a sort of House of Mercy at Brighton. Five years later she confessed to a clergyman that she, alone and unaided, had murdered her little brother. This statement she repeated to the late Sir Thomas Henry, at the Bow-Street Police Court. The public refused, however, to believe her confession, claming that the “Sisters” and Rev. Mr. Wagner had driven her mad by their High Church practices. It was also said that she was sacrificing herself to save her father. When put upon her trial she pleaded guilty, and notwithstanding all warnings persisted in that plea. The sentence of death was passed upon her by Mr. Justice Willes, who presided. It was represented to the Crown that in spite of her own confession, and the fact that her legal advisors had not pleaded insanity, the poor girl was not altogether responsible for her actions. Royal clemency was extended, and the sentence of death was commuted to imprisonment for life.

No motive for the crime was ever suggested at the time of the trial. Every one asked why should Constance Kent have killed her little half-brother, to whom it was proved she was deeply attached? Mr. (now Lord) Coleridge, her advocate, stated in court before sentence was passed that she had herself desired him to say that she was not driven to the terrible crime she had committed by any unkind treatment on the part of her step-mother. “She met with nothing at home,” said he, “but tender, forbearing love. I hope I may add, not improperly, that it gives me a melancholy pleasure to be made the organ of these statements, because, on my honor, I believe them to be true.”

In the London papers of April 30, 13 years after the crime, we find the following report:

“Dr. J. C. Bucknill, in closing the second of his Lumleian lectures on “Insanity in its Legal Relations,” before the Royal College of Physicians, said: It is a happy circumstance for us professionally that we have not often to give direct evidence of crime. It is painful enough to give negative evidence which is incriminating. The most remarkable case in which I have been concerned, not even excepting that of Victor Townley, was the case of Constance Kent, who murdered her young brother and escaped detection. After an interval of several years, a truly conscientious motive led her to confess, and the most painful and interesting duty fell to my lot of examining her for the purpose of ascertaining whether it would be right to enter the plea of “not guilty on the ground of insanity.” I was compelled to advise against it, and her counsel, Mr. (now Lord) Coleridge, on reading the notes of my examination, admitted that I could not do otherwise. By her own wish, and that of her relatives, I published a letter in the Times describing the material facts of the crime, but, to save the feelings of those who were alive at the time, I did not make known the motive, and on this account it has been that the strange portent has remained in the history of our social life that a young girl, not insane, should have been capable of murdering her beautiful boy-brother in cold blood, and without motive. I think the right time and opportunity has come for me to explain away this apparent monstrosity of conduct. A real and dreadful motive did exist. The girl’s own mother, having become partially demented, was left by her husband to live in the seclusion of her own room, while the management of the household was taken over the heads of grown-up daughters by a high-spirited governess, who, after the decease of the first Mrs. Kent, and a decent interval, became Constance Kent’s step-mother. In this position she was unwise enough to make disparaging remarks about her predecessor, little dreaming, poor lady, of the fund of rage and revengeful feeling she was stirring up in the heart of her young step-daughter. To escape from her hated presence, Constance once ran away from home, but was brought back; and after this she only thought of the most efficient manner of wreaking her vengeance. She thought of poisoning her step-mother, but that, on reflection, she felt would be no real punishment, and then it was that she determined to murder the poor lady’s boy, her only child. A dreadful story this, but who can fail to pity the depths of household misery which it denotes? At her arraignment, Constance Kent persisted in pleading “guilty.” Had the plea been “not guilty,” it would, I suppose, have been my most painful duty to have told the court the tragic history which I now tell to you, in the belief that it can give no pain to those concerned in it, and that it is mischievous that so great and notorious a crime should remain unexplained.”

JW Stapleton about the murder.